Incremental lexer for IDE

Yuras Shumovich

I’m not an active IDE user. This days I use XCode sometimes, because writing Objective-C without an IDE is a pain. Otherwise I use vim without any plugins.

But I always was interested in IDE internals. Many years ago I was working on Visual Studio debugger plugin for some proprietary RTOS, and I was impressed how huge and complex Visual Studio was. One person can’t create anything comparable. But that doesn’t mean we should not try :)

So I finally found time to experiment with some IDE features. In this post I’ll describe the roadmap and present the first phase – incremental lexer.

What I would like to achieve

The most basic IDE features are syntax highlighting, navigation, autocompletion and refactoring. To be usefull IDE should be interactive – we expect instant response to our actions. That is the most interesting aspect for me. So the feature list I’d like to experiment with:

- incremental lexing

- source highlighting

- incremental parsing

- navigation

- incremental typechecking

- type directed autocompletion

The goal is to make these work in soft real time, without blocking UI. For example, if we can’t hightlight code after an edit quickly enough, then lets show raw text and highlight it in backgroud. If we can’t show all possible autocompletions, then lets show only available ones and add more later. Basically all foreground operations should have complexity not worse then \(O(\log n)\) whatever \(n\) is.

Raw performance and memory usage are not the direct goals. Building full featured IDE is not the goal too.

Incremental lexing

Incremental lexer should maintain a list of tokens while user is editing the code. Ideally it should reuse already processed tokens.

It is not so hard, for example yi caches intermediate lexer states. On modification we just find the last valid point and restart from it.

But that way on each modification we have to process all the code from the modification to the end of the file. It is OK for highlighting though, because we can analyze the code only as far as it is necessary to hightlight visible part of the file. But we want to use results of lexing to build syntax tree incrementally, and nodes of the tree can be annotated with results of incremental type checking. We don’t want to lose all the work on each keystroke.

The solution is obvious – lets analyze code only until the next valid point. Basically, we stop when:

- we are outsize the affected area, and

- the current token parsed is equal to the cached one at this point, and

- the lexer state is equal to the cached one at this point

Conventions

(You can skip the details.)

More formally, we have a tokinizer

tokenize :: State -> String -> Result

data Result

= Partial (String -> Result Token) -- continuation

| Done Token State Int Int -- token, lexer state,

-- length of input consumed

-- and lookaheadIt never fails, instead it returns some special token representing lexical error.

Lexer maintains the current source code as a list of characters

\[C = [c_0, c_1, ..., c_n]\]

and list of lexemes

\[L = [L_0, L_1, ..., L_n]\]

where

- \(L_i = (t_i, s_i, l_i, a_i)\)

- \(t_i\) is a token,

- \(s_i\) – lexer state after reading the token,

- \(l_i\) – number of characters consumed by lexer to produce the token, and

- \(a_i\) – lookahead, number of characters lexer examined without consuming.

The following invariant should be reserved:

\[\sum_{k=0}^{n}l_i = length(C) \label{invariant}\tag{1}\]

Single edit of the source code can be represented as a tuple

\[(p_s, p_e, C')\]

where

- \([p_s, p_e)\) – interval in \(C\) to delete

- \(C'\) – list of characters to insert.

For example, deleting 5 characters starting from position 3 will look like

\[(3, 8, \emptyset)\]

where \(\emptyset\) – empty list.

Inserting string “hello” at position 3 will look like

\[(3, 3, hello)\]

Dirty region

After each edit, lexer should invalidate part of the lexeme list \(L\) by replacing lexemes from \(L_i\) to \(L_j\) with special \(D\) token representing dirty region:

\[ [L_0, ...,L_{i-1}, (D, \_, l, 0), L_{j+1},..., L_n] \]

where

\[l = \sum_{k=i}^{j}l_k - (p_e-p_s) + length(C')\]

is a length of the dirty area, lookahead is zero and lexer state is irrelevant. Note that the invariant \((\ref{invariant})\) is satisfied.

Finding \(L_j\) is straightforward, it should be the first lexeme, such that

\[\sum_{k=0}^{j-1}l_k > p_e\]

Finding \(L_i\) is a bit harder. Obviously it should satisfy

\[\sum_{k=0}^{i-1}l_k < p_s\]

but it doesn’t take lookahead into account. Lexema \(L_k\) should be invalidated whenever the edit affects any of \(a_k\) characters after it.

Lets introduce a function to calculate lookahead of two subsequent lexemes

\[lookahead(L_k,L_{k+1}) = max (a_{k+1}, a_k-l_{k+1}) \label{lookahead}\tag{2}\]

It can be easily generalized to any number of lexemes. Now the beginning of the dirty region should satisfy

\[\sum_{k=0}^{i-1}l_k + lookahead(L_0,...,L_{i-1}) < p_s\]

Lexing

Now it is time to do actuall lexing of dirty region. Lets length of \(C\) before the dirty region is \(p\)

\[p = length (L_0, L_1, ..., L_{i-1}) = \sum_{k=0}^{i-1}l_k\]

Lets feed tokinizer with the last valid state and the input

\[ Done(t', s', l', a') = tokenize(s_{i-1}, [c_{p+1},c_{p+2},...])\]

(If the tokenizer returns Partial, we should feed more input. Lets assume it always returns Done.)

Now we can insert new lexeme into \(L\). If \(l' < l\), then

\[ [L_0, ...,L_{i-1}, (t', s', l', a'), (D, \_, l-l', 0), L_{j+1},..., L_n] \]

If \(l' > l\), then \(L_{j+1}\) (and probably few more lexemes) is invalid too

\[ [L_0, ...,L_{i-1}, (t', s', l', a'), (D, \_, l+l_{j+1}-l', 0), L_{j+2},..., L_n] \]

The \(l'=l\) case is more interesting. We should chech whether we are done, so lets run tokenizer one time more

\[ Done(t'', s'', l'', a'') = tokenize(s', [c_{p+l'+1},c_{p+l'+2},...])\]

If \((t'' = t_{j+1}) \land (s'' = s_{j+1})\), then we are done

\[ [L_0, ...,L_{i-1}, (t', s', l', a'), L_{j+1},..., L_n] \]

otherwise the next lexeme is still invalid

\[ [L_0, ...,L_{i-1}, (t', s', l', a'), (t'', s'', l'', a''), (D, \_, l+l_{j+1}-l'-l'', 0), L_{j+2},..., L_n] \]

In reallity we stop after a limited number of steps to ensure user gets instant feedback. E.g. when large chunk of code pasted into editor, only the initial part of it is visible, and we can hightlight it before the whole chunk is processed, and then continue processing the rest.

Complexity of operations

In theory everything is good. But it practice, we have a number of operations with \(O(n)\) complexity:

- to find \(L_i\) and \(L_j\) we have to traverse the entire \(L\) list

- to find the first dirty region, we have to traverse \(L\) too

- to update \(C\) and to build an input \([c_{p+1},...]\) for tokenizer, we have to traverse \(C\) list

That it not acceptable for real time UI.

The solution for the last issue is when know – it is a Rope. Basically it is a tree with small substrings of the whole string as a leafs. Each intermedite note is annotated with a length of a substring, represented by the subtrees, so insert, delete and split operations can be implemented with \(O(\log n)\) complexity.

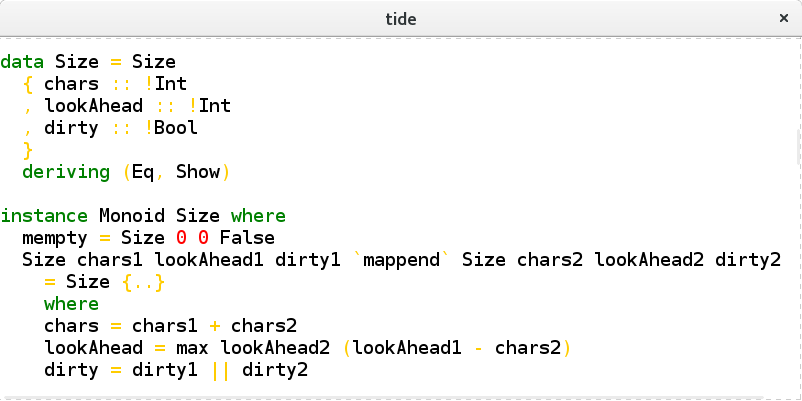

Rope can be generalized to arbitrary list with some monoid as an annotation. In our case, we can represent \(L\) as a fingertree with the next monoid:

data Size = Size

{ chars :: !Int

, lookAhead :: !Int

, dirty :: !Bool

}

deriving (Eq, Show)

instance Monoid Size where

mempty = Size 0 0 False

mappend (Size chars1 lookAhead1 dirty1)

(Size chars2 lookAhead2 dirty2)

= Size chars lookAhead dirty

where

chars = chars1 + chars2

lookAhead = max lookAhead2 (lookAhead1 - chars2)

dirty = dirty1 || dirty2Here chars represents \(l_k\), lookahead – \(a_k\) (compare with \((\ref{lookahead})\)), and dirty is True for \(D\) and False otherwise.

That way we can implement all mentioned operations with \(O(\log n)\) complexity.

Implementation

You can find the implementation on github.

- TextBuffer.hs contains implementation of \(C\),

- TokenBuffer.hs contains implementation of \(L\),

- Lex.hs implements the main lexer logic, and

- HaskellLex.hs is a simplified tokinizer for haskell.

The is also a UI based on gtk3 with syntax highlighting implemented using the incremental lexer. It is fully asynchronous, so you can edit file while it is processed in background. It also logs to the console the region processed on each step.

A short video.

Screenshot:

Final notes

It is important to make sure tokenizer consumes limited number of characters on each run. For example, multiline comments can be pretty long, but we want to provide user with instant feedback. To achieve that, we can split comment token into parts. That is the reason we have tokenizer state in the first place.

Other issue is not solved yet. Each time user enters {- into the buffer, all the rest of the file becomes a comment until user enters the closing -}. It probably requires special handling to prevent unnecessary reprocessing.