Realtime collaborative editor. Algebraic properties of the problem.

Yuras Shumovich

Collaborative editors (or RTCE) are very popular this days. There are lots of open source and proprietary solutions. So I was not surprised when I got a request to build one.

But I was surprised that I can’t find exhaustive description of technologies used to implement RTCE. Probably the best source I found here, it describes the general idea and pitfalls of RCTE implementations based on operational transformation (OT). Unfortunately it can’t be used to implement custom RTCE immediately – the algorithm is not explicitly stated, and correctness of the solution is not clear. And the original paper contains substantially more complex algorithm.

While reading different materials about the topic, I noticed that the problem has pretty reach set of algebraic properties. Exploring them allowed me to formulate the algorithm and proof its correctness. I’ll try to document the results below. Probably the most important result is a set of properties which we should prove by equation reasoning or check automatically to ensure correctness.

Document operations

Suppose we have a document \(A\), and some operation \(a\) transforms it to other document \(B\):

\[ B = a(A) \]

For example, document could be a text, and operation can insert or delete few characters in it. There is an identity operation \(e\), it doesn’t change the document.

The operation \(a\) is tightly coupled with \(A\). We can’t apply it to \(B\) or any other document. E.g. if \(a\) deletes "world" from "hello world!", then it makes no sense to delete it from "hello !". But there can exist other operation \(b\), which operates on \(B\):

\[ C = b(B) \]

And we can apply them in a row:

\[ C = b(a(A)) \label{composition}\tag{1} \]

That forms a new operation \(c\), which is a composition of \(a\) and \(b\) (note the order in composition, compare with \((\ref{composition})\)):

\[ c = a b \\ C = c(A) \]

Two operations are equivalent if they transform equal documents into equal. Identity operation \(e\) has usual properties with respect to composition:

\[ e a = a \\ a e = a \]

To make sense composition should be associative:

\[ (ab)c = a(bc) = abc \label{associativity}\tag{2}\]

But it is not commutative in general case, so \(ab\) is not necessary equivalent to \(ba\). Also each operation has an inverse because we always can undo any change.

Example: text document

As an example, lets see how operations can be implemented for simple plain text document. There are two atomic edits, one to insert at given position some string, and other to delete starting from given position a number of characters:

data Edit

= Insert Int Text

| Delete Int Int

deriving (Show)Composite operation can be just an array or atomic edits

newtype Patch = Patch

{ edits :: Vector Edit

}

deriving (Show)

instance Monoid Patch where

mempty = empty

mappend = append

empty :: Patch

empty = Patch Vector.empty

singleton :: Edit -> Patch

singleton edit = Patch (Vector.singleton edit)

append :: Patch -> Patch -> Patch

append p1 p2 = Patch (edits p1 Vector.++ edits p2)Associativity \((\ref{associativity})\) is obviously satisfied. Applying Edit and Patch to a document is trivial, so lets omit that.

Operational transformation

Suppose we have a document \(S\), and two clients at the same time apply some arbitrary operations:

\[ A = a(S) \\ B = b(S) \]

Now the documents diverged, and we need some other operations \(a^\prime\) and \(b^\prime\) to transform them into a consistent state \(S^\prime\):

\[ b^\prime(A) = a b^\prime(S) = S^\prime = b a^\prime(S) = b a^\prime(S) \]

They should satisfy the obvious property:

\[ a b^\prime = b a^\prime \label{commute}\tag{3}\]

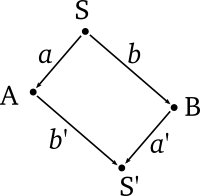

It can be represented using the following diagram:

Lets assume that there is an operational transformation \(T\) that it produces \(a^\prime\) and \(b^\prime\) for each \(a\) and \(b\) such that \((\ref{commute})\) is satisfied:

\[ (a^\prime, b^\prime) = T(a, b) \label{OT}\tag{4}\]

It is important to keep in mind that \(T\) is not necessary symmetric, so \(T(a, b)\) is not necessary equivalent to \(T(b, a)\). We should be careful not to mess with arguments, and we will draw diagrams preserving the order – the first argument always on left.

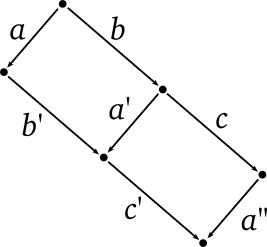

Now we should check that operation composition doesn’t break \((\ref{commute})\) under operational transformation \(T\). Lets try a composite operation as the second argument of \(T\), see the following diagram.

(UPDATE I messed things up a bit in the following proof, see here. Basically, the proof make sense for the Edit and Patch in the example, but in general case \((\ref{5c})\) can’t be proven, we should require it instead.)

Here by definition

\[ (a^\prime, b^\prime) = T(a, b) \label{5a}\tag{5a} \] \[ (a^{\prime\prime}, c^\prime) = T(a^\prime, c) \label{5b}\tag{5b} \] \[ (a^{\prime\prime}, b^\prime c^\prime) = T(a, b c) \label{5c}\tag{5c} \]

From \((\ref{5a})\) follows \(a b^\prime = b a^\prime\). From \((\ref{5b})\) follows \(a^\prime c^\prime = c a^{\prime\prime}\). Then

\[ a b^\prime c^\prime = b a^\prime c^\prime = b c a^{\prime\prime} \]

That is exactly what \((\ref{commute})\) states for \((\ref{5c})\). The same way we can prove that for a composed operation as the first argument of \(T\).

By induction we can prof that \((\ref{commute})\) is satisfied for arbitrary complex operations. It is more important then it sounds – it allows us to define operations in terms of a small number of basic operations. We define operational transformation only for them, and get it for complex operations automatically.

Back to the example

Lets defined \(T\) for the plain text document example. For insert operations, we simply adjust insert position for one of them:

transform :: Edit -> Edit -> (Edit, Edit)

transform (Insert at1 t1) (Insert at2 t2) =

if at1 > at2

then (Insert (at1 + Text.length t2) t1, Insert at2 t2)

else (Insert at1 t1, Insert (at2 + Text.length t1) t2)The case with two delete operations is a bit more involved. If ranges doesn’t overlap, we adjust starting position, the same way as for insert operations. But if they overlap, we should be careful not to delete more then necessary.

transform (Delete from1 count1) (Delete from2 count2)

| from2 >= from1 + count1

= (Delete from1 count1, Delete (from2 - count1) count2)

| from1 >= from2 + count2

= (Delete (from1 - count2) count1, Delete from2 count2)

| from1 >= from2 && from1 + count1 <= from2 + count2

= (Delete from2 0, Delete from2 (count2 - count1))

| from2 >= from1 && from2 + count2 <= from1 + count1

= (Delete from1 (count1 - count2), Delete from1 0)

| from1 >= from2

= let d = from2 + count2 - from1

in (Delete from2 (count1 - d), Delete from2 (count2 - d))

| otherwise

= let d = from1 + count1 - from2

in (Delete from1 (count1 - d), Delete from1 (count2 - d))The first two guards handle the case of not overlapping edits. The second two – when one covers another. The last two – partially overlapping edits. The mixed case, when we transform insert and delete operations, is analogous:

transform (Insert at t) (Delete from count)

| at >= from && at < from + count

= (Insert from Text.empty, Delete from (count + Text.length t))

| at < from

= (Insert at t, Delete (from + Text.length t) count)

| otherwise

= (Insert (at - count) t, Delete from count)

transform d@Delete{} i@Insert{} =

Tuple.swap $ transform i dNote that the implementation above is not the only possible one. For example I decided to preserve both edits in case of two inserts into the same position. Other implementations can e.g. prefer the first insert, or ignore both conflicting inserts.

Transforming composed operations follows the inductive logic of proving \((\ref{commute})\) for them:

transform :: Patch -> Patch -> (Patch, Patch)

transform (Patch a) b =

let step (a', b') a1 =

let (a1', b'') = transformEdit a1 b'

in (append a' (singleton a1'), b'')

in Vector.foldl' step (empty, b) a

transformEdit :: Edit -> Patch -> (Edit, Patch)

transformEdit a (Patch b) =

let step (a', b') b1 =

let (a'', b1') = Edit.transform a' b1

in (a'', append b' (singleton b1'))

in Vector.foldl' step (a, empty) bEquation reasoning and QuickCheck can be used to prove properties we developed in previous section, but we omit that.

Algorithm

Now we are ready to describe the algorithm.

Server maintains a state, which is a tuple of 3 elements \((S, n, s)\): the current document state \(S\); an integral number to identify current revision; a sequence of operations \(s = [..., a, b, c]\) applied to the initial revision to get \(S\). Server receives from clients tuples of 2 elements, an operations \(p\) to apply and a number identifying a revision to apply the operation to.

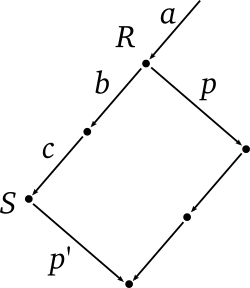

Each time new tuple received from a client, server finds the corresponding revision \(R\) and transforms \(p\) over all the operations from \(R\) to \(S\):

\[ (b^\prime c^\prime, p^\prime) = T(b c, p) \]

Server broadcasts \(p^\prime\) to all clients (we assume order-preserving channel), applies it to \(S\), increments revision \(n\) and appends \(p^\prime\) to \(s\):

\[ (S, n, s) \Rightarrow (p^\prime(S), n + 1, (s, p^\prime)) \label{server}\tag{SERVER}\]

Client side is a bit more involved. Each client maintains a state, a tuple of 5 elements: the last known server document state \(S\), the last known server revision \(n\), the operation it is trying to push to server \(a\) (in-flight operations), a buffered operation \(b\), and current local document state \(C\). Both \(a\) and \(b\) could be (and initially are) identity operations \(e\). In-flight operation is operations we sent to server, but not got an acknowledgment. All the local operations before the acknowledgment are buffered in \(b\), then client tries to push \(b\).

More formally, when local change is received, it is applied to the local document \(C\) and combined with buffered operation \(b\):

\[ (S, n, a, b, C) \Rightarrow (S, n, a, b p, p(C)) \label{local}\tag{LOCAL}\]

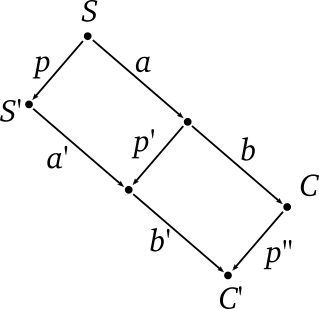

When remote change \(p\) is received form server (it is the operation \(p^\prime\) broadcasted by \((\ref{server})\) rule), and \(p\) is not equivalent to \(a\), client applies it to \(S\) to get new server document state and increments \(n\). Then client transforms \(a\) and \(b\) and updates \(C\) according the following rule:

\[ (S, n, a, b, C) \Rightarrow (p(S), n + 1, a^\prime, b^\prime, p''(C)) \label{remote}\tag{REMOTE} \] where \[ (p^\prime, a^\prime) = T(p, a) \] \[ (p^{\prime\prime}, b^\prime) = T(p^\prime, b) \]

It will be more clear from the following diagram. Here \(S^\prime\) represents new server document state, and \(C^\prime\) represents new local document state.

We need two more state transition rules. When client receives remote change \(p\) which is equivalent to \(a\), then it means that server accepted our in-flight operation. We should simply discard \(a\) (replace it with identity operation \(e\)), apply \(p\) to server document state and increment revision:

\[ (S, n, a, b, C) \Rightarrow (p(S), n + 1, e, b, C) \label{ack}\tag{ACK}\] where \[ a = p \]

And finally client should push buffered operations to server. Whenever \(a\) is equivalent to identity but \(b\) is not, client sends a tuple of 2 elements, buffered operations \(b\) and last know server revision \(n\), to server, see \((\ref{server})\) rule. Client state transition rule:

\[ (S, n, a, b, C) \Rightarrow (S, n, b, e, C) \label{send}\tag{SEND} \] where \[ a = e \land b \ne e \]

Convergence

Lets now prove that server and client versions of the document will converge eventually. First of all we notice that the client’s algorithm is built to preserve the following property for each state:

\[ (S, n, a, b, C) \Rrightarrow C = ab(S) = b(a(S)) \label{invariant}\tag{6}\]

I.e. local document state is \(ab\) far from the last known server document state. Lets prove it for each client’s transition rule. After applying \((\ref{local})\) we obviously have

\[ abp(S) = p(ab(S)) = p(C) \]

Proved. After \((\ref{remote})\)

\[ p a^\prime b^\prime (S) = ap^\prime b^\prime (S) = a b p^{\prime\prime}(S) = p^{\prime\prime} (ab(S)) = p^{\prime\prime}C \]

(We used \((\ref{commute})\) here.) Proved. I’ll omit profs for \((\ref{ack})\) and \((\ref{send})\) – they are analogous.

If client receives operations from server in the same order it sends them, then his last known server document state obviously converges to server’s document state. Now it is enough to prove that \(a\) and \(b\) (in-flight and buffered operations) will become identity operations \(e\) eventually, and we prove convergence:

\[ C = ab(S) = ee(S) = S \]

From \((\ref{send})\) follows that \(b\) vanishes whenever \(a\) vanishes. And from \((\ref{ack})\) follows that \(a\) vanishes when \(a = p\) condition is met. It means that server should acknowledge client’s in-flight operations by equivalent one. Lets prove it is the case.

Lets client state after the last acknowledge is \((S, n, e, a, C)\). Server state at the same revision is \((S, n, s)\). Now client applies \((\ref{send})\) rule, sends a tuple \((a, n)\) to the server and jumps to \((S, n, a, e, C)\) state.

At the same time server receives operation from some other client. Server applies \((\ref{server})\) rule. Lets denote transformed operation as \(b\), then server broadcasts \(b\) and jumps to the next state:

\[ (b(S), n + 1, (s, b)) \]

Midtime the client applies (a number of) local operation \(c\), according to \((\ref{local})\), it performs the next transition:

\[ (S, n, a, e, C) \Rightarrow (S, n, a, c, c(C))\]

Then client receives \(b\) from server and applies \((\ref{remote})\):

\[ (S, n, a, c, c(C)) \Rightarrow (b(S), n + 1, a^\prime, c^\prime, b^{\prime\prime}(C)) \] where \[ (b^\prime, a^\prime) = T(b, a) \] \[ (b^{\prime\prime}, a^\prime) = T(b^\prime, c) \]

At the same time server receives (\(a\), n) from client, applies \((\ref{server})\) and broadcasts \(a^\prime\):

\[ (b(S), n + 1, (s, b)) \Rightarrow (ba^\prime(S), n + 2, (s, b, a^\prime)) \] where \[ (b^\prime, a^\prime) = T(b, a) \] \[ (b^{\prime\prime}, a^\prime) = T(b^\prime, c) \]

Note that “where” clause in the last step on server exactly identical to the last step performed on client. It means that the operation broadcasted by server is equivalent to the in-flight operational on client. Client receives it and applies \((\ref{ack})\):

\[ (b(S), n + 1, a^\prime, c^\prime, b^{\prime\prime}(C)) \Rightarrow (ba^\prime(S), n + 2, e, c^\prime, b^{\prime\prime}a^\prime(C)) \]

Now client is ready to push the next operation. When all local operations are pushed and all remote operations are received, client state is \((S^\prime, n^\prime, e, e, C^\prime)\), where \(S^\prime = C^\prime\). We just proved convergence.

Demo implementation

You can find demo client and server on github. If you are interested in ready-to-use demo, then checkout cli to server and gtk ui for client Just start server and a number of clients and start typing. (Client requires theaded runtime)

The operation representation as an array of basic edits is simple. But it is hard to compare operations – two equivalent ones could be represented differently. That is why the demo compare operations by applying them to a document and comparing results. More sophisticated representation usually comes with a some kind of normalized form. See for example how it is implemented in ot package.